Van Cortlandt House Museum

by habituallychic

07 . 01 . 21

Now that we can go places again, I’ve been trying to check off some of the places I have been wanting to explore in New York. Last Friday, I took a field trip to the Van Cortlandt House Museum which is the oldest building in the borough of the Bronx and run by the National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New York. The house has seen a lot of history and I learned so much on my visit.

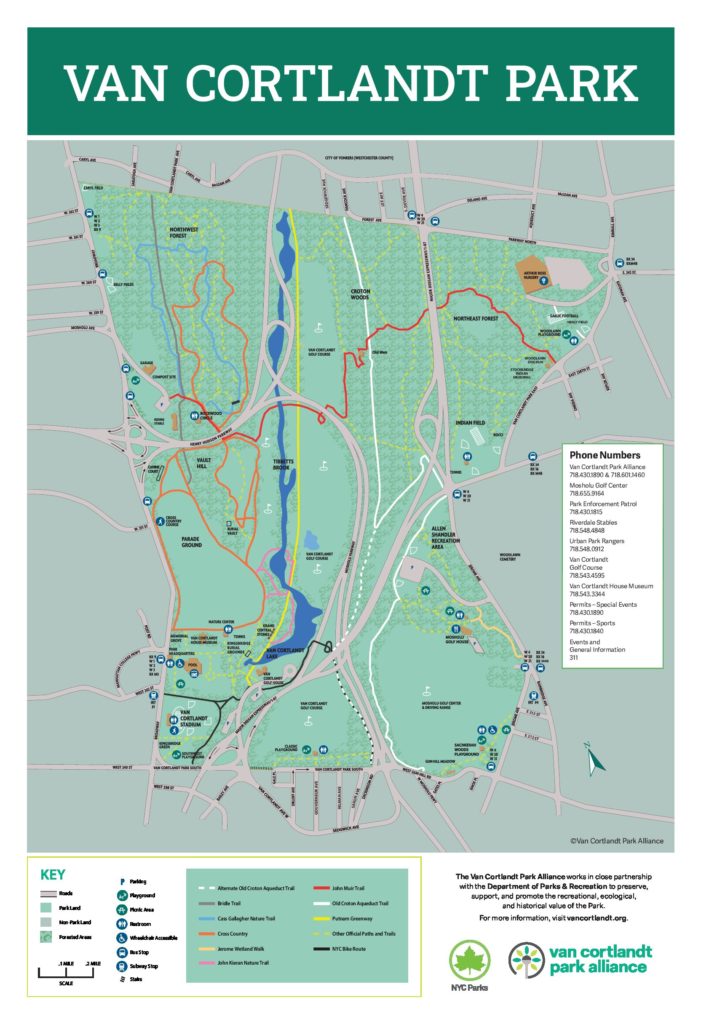

The Van Cortlandt House Museum is located in the southwestern portion of Van Cortlandt Park which was the previous plantation farmland of the Van Cortlandt family. From the Upper East Side, it was about a half hour drive in an Uber but could take longer depending on traffic. You can also drive or take 1 subway line. I chose to go the Cloisters which is part of The Metropolitan Museum of Art but you could also visit the New York Botanical Garden or even the Bronx Zoo.

The website has a full outline of The History of the Van Cortlandt Family and their Plantation which “begins in 1638 when Oloff Stevense Van Cortlandt arrived in New Amsterdam from Holland.Oloff was an employee and officer of the Dutch West India Company. Oloff was eventually considered one of the wealthiest men in New York having made his money as a merchant, brewer, money lender, and in shipping. Near the end of the 17th century, Jacobus, the youngest of Oloff’s seven children, made his first purchase of land of what would eventually become a large and profitable wheat plantation. While Jacobus may not have lived on his plantation, he did have enslaved people (both Africans and Native Americans) working here growing wheat, making improvements to the land, building barns, two mills, and building the dam that turned Tibbett’s Brook into a lake.”

“After the death of Jacobus Van Cortlandt, the plantation was inherited by his only son Frederick Van Cortlandt. In his will Jacobus leaves the plantation as well as enslaved workers to his only son Frederick. Frederick and his family were documented as living on the plantation by 1748. In his will Frederick notes “I am now about finishing a large stone dwelling House on the Plantation on which I now live”. This Georgian style house, present day Van Cortlandt House Museum, was not finished before Frederick died in early 1749 so it passed to his eldest son James with a provision that Frederick’s wife and James’ mother, Francis, may live in the house for the rest of her life or until she remarries. James’ young sisters Anne 14, and Eva 13 were also granted the right to live in the house until they married. Frederick’s will also lists enslaved people, one or more he may have inherited from his father.”

“The Van Cortlandt family’s ownership of the plantation that is now known as Van Cortlandt Park and the house now known as the Van Cortlandt House Museum ended in 1889 when Augustus Van Cortlandt sold the land to the City of New York for the park. The house is believed to have been given to the city to be used for the public good.

In 1896, the state Legislature granted custody of the house to the National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New York. The following year the mansion was opened as a public museum which makes the Van Cortlandt House Museum the oldest house museum in New York and the fourth oldest in the country. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1967 and became a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

You enter the Van Cortlandt House Museum through the gift shop where you can check in or buy tickets. Due to Covid restrictions, you go through the house on a self-guided tour with url codes that can give you information on each area of the house. I bought dried lavender that had been grown in the Herb Garden.

The Van Cortlandt family crest.

You enter the house through this small door on the side that leads you to the entry on the back side of the house.

Van Cortlandt House was also temporary home to General George Washington on several occasions during the Revolutionary War. Washington first occupied Van Cortlandt House as temporary headquarters in October of 1776 and then again in late November 1783. The house was also used during the Revolutionary War by the Comte de Rochambeau and Marquis de Lafayette. Washington’s final documented visit to Van Cortlandt House took place in November of 1783 when he and his entourage stopped overnight on their way into Manhattan to take possession of the island back from the defeated British Army.

John Adams is said to have stayed overnight on his way to George Washington’s inauguration. This means he would have traveled to the Van Cortlandt House after his own inauguration on 21 April 1789 at Federal Hall in lower Manhattan before heading back down before Washington’s inauguration on 30 April 1789. This might have been possible since it was supposedly the finest house in the area at the time.

“The spacious main entrance hall of Van Cortlandt House served as both a passageway and as a waiting area. The soaring height of the staircase brightly lit with windows on all three floors, signaled the family’s social status and wealth showing an ability to spend money on a staircase that, in more modest Colonial-era houses would have been more useful and less beautiful.”

“The original wide yellow pine floorboards in the entrance hall are protected by a painted floor cloth. These cloths are made of canvas painted with several layers of paint to make them stiff and durable.” I stayed at a historic house in Colonial Williamsburg that also had this exact type of painted floorcloth.

The future King William IV of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland dined at the Van Cortlandt House as a young man and supposedly gave the carved wooden birds as a gift to the family.

Fun fact from Gettysburgian, “As a midshipman in the Royal Navy, Prince William served in New York during the American Revolution making him the only British Royal to have ever visited the American colonies. During the war General George Washington approved a plan to kidnap Prince William, but the British got word of this and the plan was thwarted.”

But according to the Van Cortlandt House Museum, “The large carved wooden eagles on either side of the front door stood on posts on either side of a gate to the grounds of Van Cortlandt House to the east. These gateposts and the eagles were removed from this entrance around the time that Van Cortlandt House was left to the City of New York by the Van Cortlandt family. The gate posts were cut down to make pedestals for the eagles which were brought into the house. Of all the things in Van Cortlandt House that were once owned by the Van Cortlandt family, these eagles never left. “

The house retains most of its original interior architectural details.

The formal East Parlor is of exceptional fine Georgian design and “would have been the scene of the family’s most festive and special entertaining.” The portrait to the left of the fireplace is of the third owner of the house, Augustus Van Cortlandt (1728-1823), painted by John Wesley Jarvis, in about 1810.

“The highly carved mantelpiece, c. 1760, is the work of two anonymous New York carvers who may have apprenticed or worked as journeymen in London. This decoration is believed to have been added by James Van Cortlandt, around the time of his marriage to Elizabeth Cuyler of Albany, New York. The remodeling was carried out in the very fashionable rococo style with ornate carving surrounding the fireplace.”

“As the scene for various types of entertainments, the East Parlor would have been filled with beautiful yet versatile furniture. When not in use, card tables and tea tables fold up for placement against the walls, leaving the center of the room open for large gatherings such as a dance.”

Even with special shades on the windows to protect the rooms from the sun, they still have beautiful light throughout the day.

“The table beneath the large gilt mirror is a recent gift to Van Cortlandt House Museum. It is a five-legged mahogany card table made in New York c. 1760 and is unusual in that it has five legs rather than the four usually found on folding card tables. It is this fifth leg that indicates to curators and collectors of antique furniture that the table was indeed made in New York. A gift of Mr. William H. Savage in loving memory of Carolyn Mackie Savage and Carolyn Van Cortlandt Martin, the table has been passed down through several generations of the Van Cortlandt family.”

The view is of what would have been the front of the house.

“The less-formal West Parlor would have hosted family meals and casual gatherings. The bright orange and blue paneling is the exact color of the room at the end of the 18th-century as determined by microscopic paint analysis. In this less-important room, decoration was achieved with color rather than expensive carving, as in the East Parlor.”

“Across the room you will see a desk with three large Delft tobacco jars. Each is labeled to identify what was once held inside the jar. No 12 would have been a special blend sold only by the tobacconist who once owned the jar. Rappe (French râpé, “grated”) is the name given to a coarse, pungent snuff made from dark tobacco. Rappe snuff was so coarse that people who preferred it had to carry graters with them to turn it into a fine enough powder to use. Sto. Domingo indicates tobacco that had been grown in Santo Domingo on the island of Hispanola which was known as a source of fine tobacco in the 18th-century.”

I looked through many old photos of the Van Cortlandt House Museum and it was interesting to see that they do change up the location of the furniture in the rooms to tell different stories. Even though the house would not have had Christmas decorations at the time it was built, they do decorate for the holidays which makes it another lovely time to visit.

The West Parlor also reflects the family’s Dutch heritage with the blue and white tiles that surround the fireplace.

The green chairs are usually located in the entry and halls for visitors but have been moved due to Covid restrictions.

The cupboards contain china and glassware owned by the family.

So many lovely trees surround the Van Cortlandt House Museum.

The family would have used the main staircase to access the upper floors while enslaved people and servants would have used the back staircase.

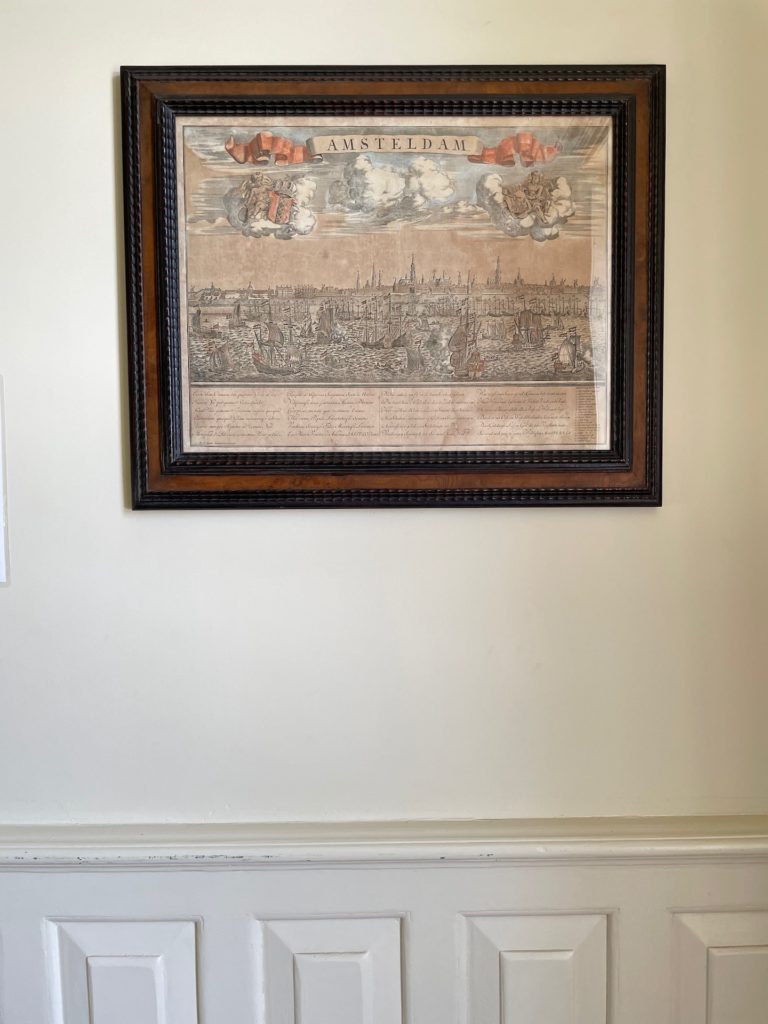

There are a lot of wonderful old engravings of New York on the stairs and hallways of the house.

The second floor landing is quite a large area and has a window seat that overlooks what would have been the main entrance to the house.

Each room is protected by a large gate that is over four feet high. I assume this is to protect from the theft of antiques in case someone were to break into the Van Cortlandt House Museum.

The West Chamber or bedchamber, the “best” bedchamber, is the one most likely used by George Washington on his various visits to Van Cortlandt House and also known as the Washington Bedroom.

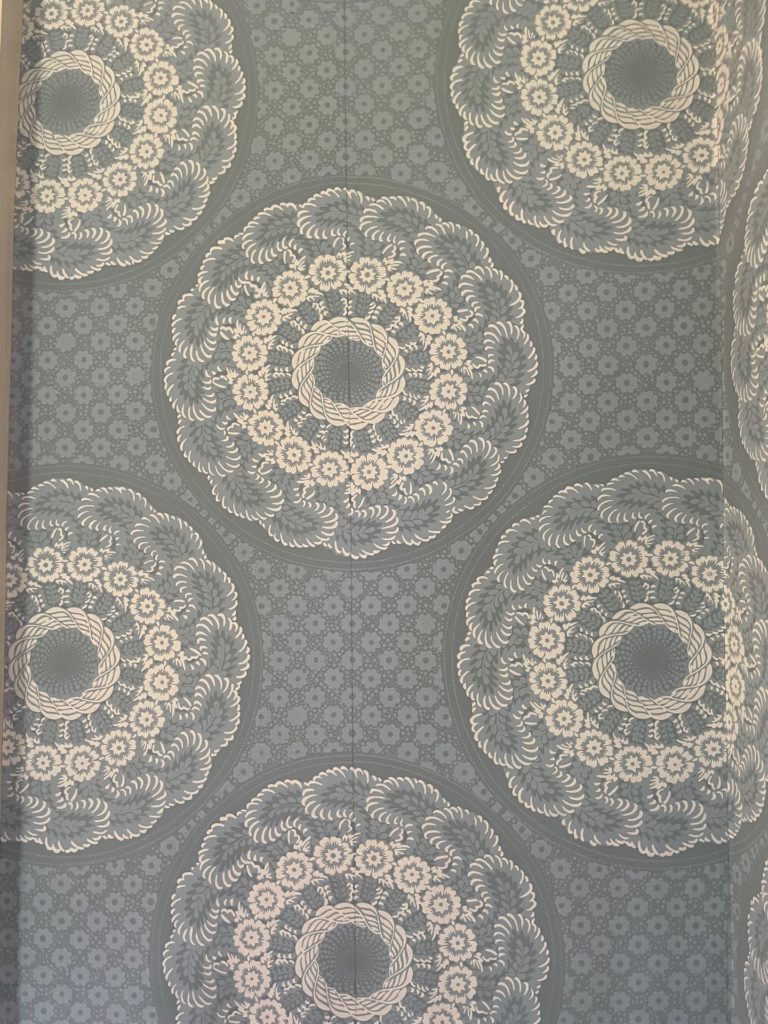

“The West Chamber is furnished with matching bed and window hangings in what is known as a “drapery” style. This style allowed for the curtains at the windows to be drawn up to allow light into the room during the day as needed. The bed was also hung with curtains that could be raised or lowered to help keep the sleeper warmer in winter or for more privacy. While earlier versions of bed hangings were often made of wool or silk, these fabrics were not washable and were often prone to infestations of fleas and bed bugs. By the 18th century bed curtains of wool and silk were replaced with cotton or linen fabrics which could be washed periodically. The hangings in the West Chamber are made of fabric known as chintz which is cotton printed by hand and finished with a light shiny glaze or polish. The pattern of these hangings is from the archives of the Dutch East India Company which was one of the major importers of printed textiles to Europe in the 18th century.”

“The mahogany knee-hole dressing table, c. 1770, located beneath the mirror descended in the Van Cortlandt Family. It was made in Massachusetts. The burl walnut chest of drawers to the left of the door is English, c. 1725 not shown). It is said to have belonged to Mary Van Cortlandt Horne, a daughter of Frederick Van Cortlandt, who built the house.”

“Keep in mind, though, that the furnishing and decorations in the room were not here during Washington’s time. The furnishings in this room, and throughout the house, were collected for the museum based on the choices that would have been available to a family such as the Van Cortlandts in the second half of the 18th-century and the early years of the 19th-century.”

A view of the front walk from the second floor landing.

Amsteldam later became Amsterdam.

“In the 18th century, celebrations and social gatherings, such as a ball or dance, frequently lasted for more than a single evening. Because of the great difficulty with travel, party guests would have been offered lodging with the host. When offered lodging, most guests, whether due to distance traveled or reluctance to leave a festive party, accepted the invitation to spend the night. The East Chamber has been made ready for visiting guests who have traveled to Van Cortlandt House with an infant child.”

“The William and Mary chest of drawers, in the far corner, and matching dressing table, between the windows, were both made in New England c. 1710. A looking glass usually hung over a dressing table where men and women sat to apply make-up and groom themselves for appearances in polite society.”

“The East Chamber is “furnished” or hung with bed and window curtains made from a reproduction of an English, wax resist-dyed fabric which many Colonial New Yorkers used in their homes. This style of upholstering a room matching fabric is called “en suite” with furniture and curtains created from or covered in a single fabric. This style was very popular in the 18th-century. An elaborate display of imported fabric such as this was possible only in the home of a wealthy family.”

“The story of the dollhouse begins with the friendship of two little girls, Caroline Homans and Mary Mansfield. Caroline and Mary, born two months apart in 1818, were, according to a note that came with the dollhouse, the “most intimate of friends”. Caroline Homans died in November of 1837 at the age of 19. Mary named her daughter, born in 1843, Caroline Homans Patterson in honor of her childhood friend. In 1847, Dr. John Homans, III gave the dollhouse to Caroline Homans Patterson the namesake of his only daughter. Caroline Patterson never married and had no children of her own to inherit her dollhouse. “

“Very little is known about the dollhouse before it was given to Caroline Homans Patterson in 1847. Had it been made for the original Caroline Homans? Had she inherited it from her mother or perhaps an aunt? We simply do not know. What we do understand about the house is that it was made at a time when only the wealthiest of families could afford the luxury of such an elaborate toy.”

“The other mystery surrounding the house are the dates 1744 and 1774 which are painted on the side rails of one side of the house. These dates do not correspond to any births, deaths, or marriages associated with the Homans family that have been found to date. Research into the history of the Dollhouse and the Homans family will continue in the hopes that we can find more to the story of this charming piece of the Museum’s collection.”

The National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New York also have a Dollhouse Project to furnish the house with more pieces and put it on display in another location for everyone to enjoy from all sides.

I love the old wood floors and these stairs to the third floor.

The third floor landing.

“The plain Unfinished Attic is unheated room was most likely used as a storage area and possibly as a sleeping chamber for the enslaved people who worked in the household. When it was used for sleeping, the chamber was likely furnished with a very simple table and chair and a low bed or a grass mattress placed on the floor. As such a large room, it would also have been a shared space for both sleeping and storage.”

When I first took photos and videos of this room, a green glow appeared by a spinning wheel by the left window. I thought to myself that this place could be haunted. I’m glad I researched this after my visit and not before because according to The Hauntings Of Van Cortlandt Park and other sites, visitors have reported “doors closing on their own, disembodied whispers can be heard, and apparitions are sometimes seen in the building.”

“This room is referred to as the unfinished because of the unfinished state of the walls. You can see that the framing of the house was left exposed in this room unlike others in the house which are finished off with plaster or wood paneling. Attic rooms such as this one and the nursery would have been finished off as needed as the family or need for space grew.”

“This room is currently being used much like it’s original purpose, as a storage room for extra furniture, spinning wheels, and other household items.”

“For many years it was felt that The Nursery had seen the least number of alterations since the house was built in 1748. In the winter of 2001, a closer examination of the room raised many questions surrounding its history. With little evidence beyond the existing wall surfaces, which may date to as late as the early 20th century, these questions may never be answered. The present paint colors were determined through microscopic analysis at several key points in the room. The wood trim exhibited a variety of paint layers with the oldest being the dark blue gray. With few clues as to how or even if the Van Cortlandt family used this space, it was decided to retain the long-standing interpretation of this room as a nursery.”

There have been reports of dolls getting up and walking on their own or disappearing and reappearing days later.

“In the 18th-century, children seldom participated in the social world of adults. Instead, children were relegated to a room such as this which was used as a sleeping chamber, a playroom, and a schoolroom. It is likely that the children ate many meals in the nursery or in the kitchen and did not join their elders in the dining room downstairs. It is unlikely that this room was ever used as a nursery by the Van Cortlandt family because the youngest children to have lived in the house as their primary residence were Anna Maria and Eve who were 14 and 13 when they moved into the house. They would have shared the second-best bedroom, the East Chamber on the second floor.”

This door in The Nursery leads to an unfinished room and then the Slave Quarters. When I first started my self-guided tour of the Van Cortlandt House Museum, I could hear two other women upstairs who had started their tour before me. When I got to this part of the house, I was completely alone. I didn’t feel any spirits or ghosts but I definitely thought at one point that I wanted to go before “someone” closed me inside this area. Later, I read that doors have closed on their own and people have felt a hand on their shoulder. I’m really glad this didn’t happen to me because I probably would have passed out.

“These attic rooms were studied by Dr. Bernard Herman of the University of Delaware in his examination and analysis of the house in February of 1994. The ell attic offers some of the most interesting insights into the social history of Van Cortlandt house. The unheated garret rooms with their board walls and original doors are built using wrought nails, a sign of mid 18th-century construction. The plan of the north attic and the size of the individual rooms supports the idea that this space provided quarters for household servants. The practice of housing servants in unheated rooms tucked away in garrets is well documented in eighteenth and nineteenth-century houses throughout the region of the middle colonies including New York.The presence of such rooms in the Van Cortlandt House is significant not only for what they tell us about historic living conditions and differing lifestyles under a single roof but also for their remarkable state of preservation.”

“The room interpreted as slave quarters is adjacent to the back or service stairs from the second to attic floors in the Dining Room wing. The room is sparse with no decorative finishes, no heat, and no light other than what comes in through the door when it is open. There are two sets of broad shelves along the north and south walls which were most likely used as sleeping bunks. A third narrower shelf along the north wall may have been used by the occupants of the room for storing a few personal items. The beds are made with linen ticking mattresses stuffed with paper to simulate corn husks, a single coarse linen sheet, and a single wool blanket. Personal possessions include a madder red and indigo blue woolen Romal kerchief that would have been used either as a head wrap or folded into a triangle and worn over the shoulders to cover the bosom and a small strand of chevron glass African trade beads. A bunch of dried lavender has also been hung in the room as insect repellant and to help freshen the air of the windowless room.”

“Although we do not know which of the enslaved people owned by the Van Cortlandt family would have used this room as their sleeping quarters, it can be assumed that it was used by enslaved females working in the house although not the cook. It was most common for the cook to have slept in the kitchen which was originally in a separate building more or less where the Caretaker’s Cottage is located today.”

“While walking through Van Cortlandt House Museum, consider that there would be no house were it not for the labor of enslaved people. While Frederick Van Cortlandt is credited as the builder of the house or having built the house, it is more accurate to say that he had the house built. In 1748 Frederick and his family were already living elsewhere on the plantation although the exact location is unknown. He would have taken an active role in designing the house and overseeing the construction, but it is most unlikely that Frederick, at nearly 50 years of age, was not moving fieldstones or hewing timbers as his house was being built.”

“Even after the family moved in to the house, sometime after 1750, they would have relied on the work of enslaved people for cooking, cleaning, laundry, and other aspects of daily life such as bringing water in and out of the house and keeping fireplaces supplied with wood and clear of ashes. Keeping the house warm took a tremendous amount of labor. A household in a northern colony like New York used an average of 35 cords of wood per year. A cord of wood is a neatly stacked pile measuring 8 feet long by 4 feet high and wide. The more fireplaces in a house, the more firewood used. Van Cortlandt House had above the average number of fireplaces with 7 exclusively for heating and at least one more for cooking and possibly another dedicated to heating water for laundry and bathing. This number of fireplaces could easily have doubled the family’s consumption of wood to 70 cords per year. Every piece of firewood started as a tree that had to be felled, cut into manageable pieces, stacked to dry, moved closer to the house, and then brought into the house. This one task is representative of the many tasks that would have been performed by enslaved people day in and day out at Van Cortlandt House.”

“The Dutch Room is a representation of a 17th-century dwelling in New Amsterdam, the Dutch colony established on Manhattan Island. The room was created in 1918 by The National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New York from what was originally a third bed chamber”

“An all-purpose chamber such as this provided cooking, eating, and sleeping space for a middle-class family.”

“The painted kast, or cabinet was made in the Hudson River Valley c.1700. Only six of these painted kasten (plural of kast) are known and each was made for a family of Dutch descent. A similar kast is on exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Kasten were used to store linens and valuable textiles.”

“The traditional Dutch nook bed kept parents snug in the top compartment and children warm below by keeping body heat inside.”

I love the simplicity of the back servant’s staircase.

“After extensive research and painstaking restoration, the Dining Room has been brought back to how it appeared during the ownership of the house by Augustus Van Cortlandt (1728 – 1823) the youngest son of Frederick and Frances Jay who was the third owner. Augustus inherited the house upon the death of his older brother James in 1781.”

“The room as it is seen today represents the height of post-Revolutionary War Federal elegance. The side wall and border papers, found preserved beneath later wall finishes, is a copy of the original French paper manufactured by the firm Jacquemart et Bénard c. 1820. The earliest wallpaper discovered during the exploratory phase of the restoration project was dated c. 1750 based on George II tax stamps found on the back of the paper. The other major changes to the architectural finishes of the room were removal of the c. 1840 Greek Revival plaster molding and a mantel that research indicated was not original to the room but was given to the National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New York in 1896.”

“These features were removed because remnants of the original crown molding and fireplace wall paneling were discovered during restoration of the room. The crown molding was recreated as was two-thirds of the fireplace wall paneling. The original paneling is the section to the left of the mantel. You may also notice there is a small area where the ceiling is higher. This shows the original ceiling height. During the c. 1840 renovations to the room, the ceiling was lowered to help visually minimize an east to west slope that developed over the years as the house settled. To restore the entire ceiling to the original height proved to be too great a challenge so the decision was made to show it in this one corner which also revealed the full height of the original paneling.”

“Furnishings in the Dining Room have also been reinterpreted to represent those which may have been used in the room during Augustus’ ownership. Some of these furnishings, Van Cortlandt family objects, were used in the previous interpretation of the Dining Room. The tall chest of drawers between the windows to the right of the room and the knife boxes on the side board are both Van Cortlandt family objects. The table, four of the chairs, and the settee were formerly in storage at the Headquarters of The National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New York, quietly waiting restoration and a return to useful life at Van Cortlandt House. The other two chairs were purchased at auction to match. These pieces have all been upholstered in horsehair, a very common textile used on seat furniture in the 18th and 19th-centuries.”

Dining rooms were not common and having this defined space was another sign of the Van Cortlandt family wealth.

I bought a few bookmarks in the gift shop that were made from scraps of wallpaper collected during the wallpapering of the dining room.

“The original paper c. 1820 was discovered on the west wall of the dining room beneath a later plaster wall. This discovery came as the Dining Room was being restored and was a complete surprise because there was no known record of wallpaper ever having been used in Van Cortlandt House.”

“The paper was originally printed by the French firm Jacquemart et Bénard and was chosen by Augustus Van Cortlandt. This reproduction was created by Adelphi Paper Hangings from samples of the original paper removed from the Dining Room wall.”

From Adelphi Paper Hangings, “the dining room wallpaper reproduced here was a later, 19th century addition. By this time American clients viewed France, rather than England, as the preferred source for high end wallpapers. The original Jacquemart et Bénard pattern (#5063) is an excellent example of how significant depth and variation can be achieved when using only two printed colors on a ground.”

Another view of the main stairs before heading outside.

“All of the plants in the Colonial Revival Herb Garden were grown and used in the New York area in the 18th century. Most households kept a small kitchen garden with herbs, vegetables, and flowers for use in the home. The herbs were used for seasoning food and for medicinal purposes. This formal knot garden with miniature boxwood shrubs forming planting beds was installed in the 20th century as a display garden for plans which were known to have been used during the Colonial period.”

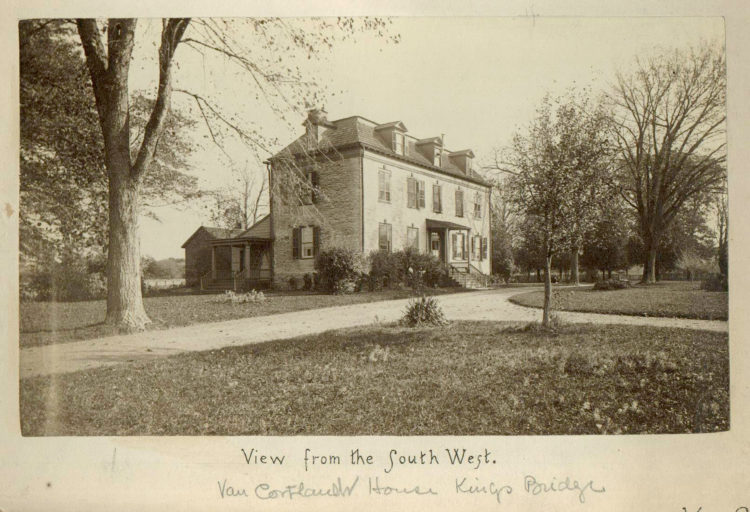

Via Lehman College, “The exterior of the house is constructed of dressed fieldstone with red brick trim around the windows. Carved grotesque faces, known as gorbels, serve as window keystones. They were a typical early design feature used in Holland around the time of construction. The upper windows of the house have seven dormers in all. A front stoop is another Dutch feature. Robert Moses demolished the formal Dutch garden and steps just south of the mansion, in the early 1970s for construction of the swimming pool just to its west.”

This is the side porch on the side of the Van Cortlandt House Museum where there are goats you can visit after you tour the house. They are in residence through September to eat invasive plant species like burdock, poison ivy, and porcelain berry that grow in the area. They were lounging under a tree when I visited and I didn’t get a good photo of them.

The original drive up to the house.

The Van Cortlandt Park near the house has cricket fields and is very open but there are beautiful old trees inside the gates of the Van Cortlandt House property.

It’s amazing that something this historic sits inside the third largest park in New York.

General Josiah Porter (1830–1894) is reputed to have been the first Harvard College graduate to enlist in the Union Army during the Civil War. He was made a first lieutenant in the Massachusetts Volunteers in 1861 and promoted to captain that same year. In 1865, he commanded the 22nd Regiment of the National Guard of New York, and in 1867, received the rank of major. Porter’s distinguished service led him to be promoted to colonel in 1869, and in 1886 to major general and adjutant general—the highest ranking military official in the New York National Guard.

You will want to double check the hours and days of admission before you head to the Van Cortlandt House Museum in the Bronx. Right now, it is only open Friday to Sunday and can be closed due to bad weather or special events. Admission is a very low $5 which makes it a reasonably priced outing for the entire family. I hope you considering the next time you are looking for something to do in New York.

All photos except the first photo are by Heather Clawson for Habitually Chic.