My Visit to Marie-Antoinette’s Private Chambers at Versailles

by habituallychic

08 . 13 . 23

One of the more special things I did in Paris in April was stay at Le Grand Contrôle Airelles Château de Versailles hotel which included private after hour tours of Versailles. There are two different tours that are possible for the first evening of your stay, the King’s Apartments or the Queen’s Apartments, and depend on which day you arrive. I was lucky to be scheduled for the Queen’s Apartments which included Marie-Antoinette’s Private Chambers. What I didn’t realize at the time of my tour was that they had recently undergone a renovation and would not be open to the public until the end of June.

Visitors to the Palace of Versailles will once again discover a series of rooms shrouded in mystery within the former royal residence. Several years of research and restoration have reawakened the richness and coherence of an eminently feminine suite of rooms spanning two floors of the Palace.

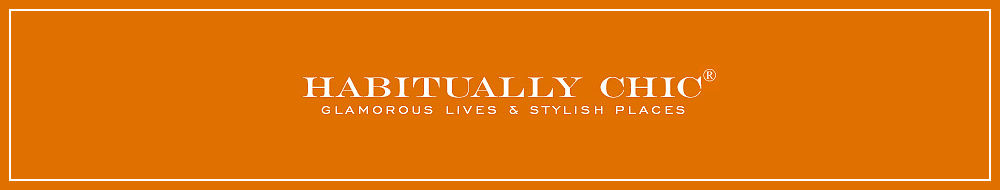

The two-story suite of smaller rooms with windows looking out upon an inner courtyard lies behind the the Queen’s State Apartment. The lower floor of these personal quarters comprises two rooms reserved for the sovereign. A chamber known as the “Méridienne” took its name from the nap taken during the middle of the day. They were first decorated by Marie-Antoinette starting in 1774 and previously had a white and then pale blue silk decor but have just been refurbished thanks to extensive research by curators who made it possible to reproduce the final lilac-hued textile decoration, enriched with varied tones of green that adorned the room under Marie-Antoinette.

The décor of this room, among the most precious in the Palace, evokes the joy of the royal couple upon the birth of their first son. Already with one daughter (Mousseline), Marie Antoinette fell pregnant again; the king was eagerly hoping for a male heir. Well aware of his wife’s need for privacy, Louis XVI wanted to please her. In 1781, he offered the queen her own petit appartement, just behind the royal bedroom. Here, she would have time to herself and rest.

Shortly after her arrival in Versailles in 1770, Marie-Antoinette took as her own the first-floor apartment of Marie Leszczynska, as well as several private rooms located on the other side. A bold young lady with unabashed tastes and keen appreciation of her rank as Archduchess of Austria and future Queen of France, she quickly ordered work to beautify her quarters. Her demanding and impatient nature even sparked disapproval from Ange Jacques Gabriel, First Architect to the King.

The successive refurbishments of the private chambers became more and more frequent, testifying to the desire for privacy felt by a vivacious young woman with an innate taste for independence. In these chambers, the queen’s true living quarters accessible only to the chosen few, Marie-Antoinette enjoyed respite from the trials and tribulations of court life and spent time with her children and her intimate circle of friends.

She never ceased to transform, extend, refurbish and beautify her chambers until 1788, indulging her passion for interior design. She arrayed these rooms with especially elegant furnishings, illustrations of the harmony and perfection of the French decorative arts at the twilight of the Ancien Régime.

“She went to her own furniture stores and ordered the winning scheme in lilac – a color she had fallen for so heavily that she also asked the embroiderer Desfarges to provide her with textiles in the same shade for her apartments in Compiègne.”

“The walls of these rooms were painted blanc du roi, a pale, matt and velvety grey often seen as synonymous with Versailles. Its central cosy alcove, lined with two-way mirrors, is flanked by french doors decorated in bronze garlands, each closed by a large lock – a masterpiece of gilding by Gouthière – engraved with the royal couple’s coat of arms.” via World of Interiors

“The lilac pou-de-soie fabric used in the original set was discovered by almost archaeological methods: microscopic purple fragments, dug out from under the upholstery tacks of the armrests, were retrieved and analysed to discover their composition. These scientific findings were compared with photos of the Compiègne furniture – pieces that, having escaped the Revolution, were now held at the Hermitage in St Petersburg.” via World of Interiors

“Armed with this research, the silk weavers of Lyon, Tassinari & Chatel (now owned by Lelièvre), supplied the room’s alcove fabrics, from curtains and armchair covers to the brocades of the niche daybed and its cushions. Meanwhile, Declercq was responsible for the rich passementerie of the soft furnishings; all the fringing, twists, tassels and thick braids in a thousand shades of green – the queen was particularly fond of soft green – that border the curtains and armchairs.” via World of Interiors

“Jérôme Declercq handled the decoration personally. ‘What I am most proud of is not so much the technique, but this subtle colour that was so difficult to get right,’ he said. ‘I think we have succeeded in bestowing the room with a real charm. It’s refined, it sings, it dances!’ Thus, the cabinet was entirely transformed in style from delicate to flashy, from a faded, gentle blue to this burst of couture colour – a tribute to its occupant’s love of excess.” via World of Interiors

The daybed’s bolster is enriched with complex tassels and the braid of several acid greens – all the trimmings were designed by Declercq Passementiers.

“From 1782 onwards, Jacob delivered the room’s furniture one item at a time: first a bergère, then a dressing screen, a stool and, finally, three extravagant armchairs engraved with sphinxes and torchères. On the armrests, we find the heads of Pekingese dogs, a breed well loved by the queen. At the heart of the room, she placed a bronze-and-petrified-wood pedestal table gifted by her sister, the Archduchess Maria Cristina of Austria; here, as well as on the mantelpiece, she would display her collection of Chinese lacquerware alongside her favourite knick-knacks.” via World of Interiors

The queen would move from the gigantic bedroom to her boudoir via a tiny door, cut invisibly into the wall’s brocade and panelling; this hidden exit would then lead her to the nursery down a narrow corridor, one that later allowed her to escape when rioters stormed the château.

One of the most amazing parts of our private tour of the Queen’s Apartments was that we were able to peek out of one of the jib doors behind the Queen’s Bedchamber.

The Bedchamber is the most important room in the apartments and is where the Queen spent most of her time. It was where she slept, often with the king, and in the morning she received guests here during and after her toilette which, like the King’s getting-up ceremony, was a courtly affair controlled by strict etiquette.

It was also here that the queen gave birth, in public, to the Princes and Princesses of the Realm. The word “public”, however, is misleading, since in reality very few people were admitted to the bedchamber while the queen was giving birth. Only doctors, ladies in waiting, the governess of the Princes and Princesses of the Realm, the Princesses of the royal family and a few members of the church were allowed to enter. The rest of the Court waited in the other rooms in the Apartment, whose doors were all symbolically left open. The queen was placed on a labour bed brought in specially, and was hidden behind a screen or canvas tent. After giving birth she was placed back in her own bed while the whole court filed through to present their compliments. Nineteen Princes and Princesses of the Realm were born here between 1682 and 1786, and two queens died here: Maria-Theresa in 1683 and Marie Leszczyńska in 1768.

The decoration in the room still reflects the three queens who once occupied it. The partitions on the ceiling date back to the reign of queen Maria-Theresa, while the greyscale painting by Boucher and the wood panelling were added for Marie Leszczyńska. These elements survived the reign of Marie-Antoinette, who replaced the furniture and fireplace and put up paintings of her mother Empress Maria-Theresa and her brother, Emperor Joseph II.

The jewellery cabinet commissioned to Schwerdfeger by Marie-Antoinette has been placed in its original position in the alcove to the left of the bed. Other pieces of furniture which were lost have been replaced by similar items, such as the sofa delivered for the Countess of Provence, the queen’s sister-in-law. The fabrics hanging on the bed and walls were re-woven in Lyon using the original patterns and the bed and balustrade have been remade using ancient documents.

Because we could not actually go out into the Queen’s Bedchamber from the Private Chambers, we had to go up one set of stairs to see the Bedchamber and Méridienne and then back down again so that we could go up a separate servant’s staircase to see the other rooms.

As of 1774, the queen laid out a series of smaller rooms which were reserved for her personal use, as well as for her Principal Chambermaids and servants. The two stories were connected by narrow staircases, including the Billiard Staircase, located behind the alcove in the Queen’s Bedchamber. Following extensive archival research into the use and hierarchy of these rooms, as well as the appearance and production of the original Toile de Jouy fabrics during the reign of Marie-Antoinette, these rooms will all be restored, refurnished and embellished with new fabric adornments.

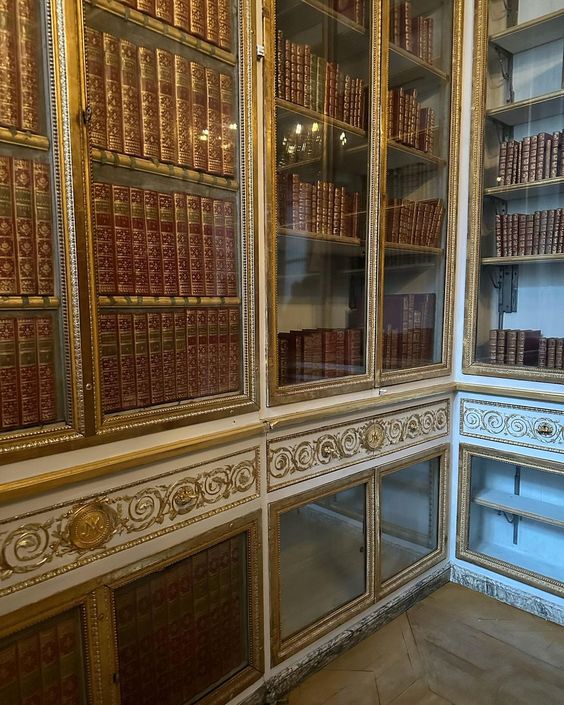

Marie-Antoinette had already been queen for five years when, in 1779, she requested the renovation of for her library. The library she had had fitted out as dauphine in 1772 was first hastily enlarged, as can be seen from the design of the parquet floor, which still traces the outlines of the previous library. A new décor followed, richer and more in keeping with her rank: gilding in dual shades of green and yellow gold upon a surface painted a pale grey hue known as “blanc du roi”. Naturally, the Queen’s monogram is omnipresent. Decorations also include the French royal coat of arms and two-headed eagles, a reminder of Marie-Antoinette’s Habsburg roots.

The new library also featured some noteworthy technical innovations: a unique rack-and-pinion system made it possible to adjust the height of the shelves holding the books, a stove, refillable from the outside terrace, was concealed beneath a window, and the heavy trompe-l’œil doors were supported by reinforced hinges, the edges of the leaves coated with velvet to prevent dust from damaging the volumes. Two years later, an annex to this library was created from a room leading to the Gold Room that was once used by the queen’s chambermaids.

The wing housing the Gold Room is a 1699 addition to Le Vau’s envelope, splitting the Queen’s Courtyard and creating the Dauphin’s Courtyard to the west. This wing was built to accommodate the apartment of the Duke of Burgundy, father of Louis XV, who wanted to be closer to his wife’s lodgings in the Queen’s State Apartments. The layout of these rooms was changed several times for Marie Leszczynska, who installed a bathing room here as of 1728.

The condition of this part of the private chambers remained unchanged until 1779, when Marie-Antoinette called on Richard Mique to create a new décor for this ample room. To take advantage of the little light that filtered through the windows giving onto narrow courtyards, Mique created an alcove, which he lined with mirrors. Meanwhile, Jean Charton, a silk manufacturer from Lyon, wove sumptuous silk hangings with gilded medallions and floral motifs based on designs by Jacques Gondouin to decorate the walls. To furnish the room, Jean-Henri Riesener, the illustrious German cabinetmaker based in Paris, supplied a set of six pieces including a table, a folding secretary and a chiffonier designed as a bookcase.

In 1781, Empress Maria Theresa left Marie-Antoinette her collection of Japanese lacquer objets d’art, which sparked a new passion in the queen, inspiring her to start her own collection. Marie-Antoinette decided to display these pieces in her great private chamber, but the fresh, flowery décor of silk wall hangings clashed with the deep gold and black of the lacquers. She thus demanded that the room be redecorated. The new décor, delivered in 1784, is the one we know today.

“The private space of Queen Marie-Antoinette, carefully preserved at the heart of the Versailles institution, is both the most compelling subject for anyone interested in the last days of the monarchy, and the most difficult one to recreate. It is indeed a question of recreating this world of absolute sophistication, since it had largely disappeared and, to further complicate the task, left very little trace in the archives. A lengthy process of cross-checking blueprints, suppliers’ accounts, orders and various documents has provided a reliable picture of the layout of these apartments, of these “private chambers” whose very name fires imagination. The hoped-for reward is that visitors will have the precious illusion of entering a place that the queen has just left.”

Laurent Salomé

Director of the National Museum of the Palaces of Versailles and Trianon